Our best wishes go out to Russell and his daughter. Read there story here:

THE images of his daughter are as vivid in his mind as any photograph he has ever taken. At age 14 she is on her bed covered in blood.

THE images of his daughter are as vivid in his mind as any photograph he has ever taken. At age 14 she is on her bed covered in blood.

The room, the one she wouldn’t let him into for weeks, is a mess. Dirty clothes line the floor and among the debris are empty bottles of alcohol and drugs. Hard drugs. He asks her where the blood has come from.

“I’ve been hitting myself with a stick,” she says, big black rings under her eyes. “Why?” he asks. “Because it makes me feel better,” she says.

As a young adult, she’s wandering the streets of Perth at 2am. She hasn’t been home for weeks.

Police, who find her naked and beaten like a “wild animal”, admit her to Royal Perth Hospital. They say she is too confused to make a statement. At least he can take her home, he thinks.In her early 20s, she is catatonic in a basement ward at one of WA’s biggest hospitals. He finds the “horrible” dumping ground is riddled with cockroaches. The doped-up patients range from the very young to the very old. One psychiatrist visits for about one hour every day. During this short visit, the patients clamour for attention. “It’s like watching a group of starving people desperate for a United Nations food drop,” he thinks.

Now, aged 23 and recovering in Sweden, his daughter is finally getting the help she needs.

“The help she couldn’t get in Perth,” he says.

The stigma associated with mental health issues has prevented us all from putting it front and centre. Shame on me, as I was one of those people.”

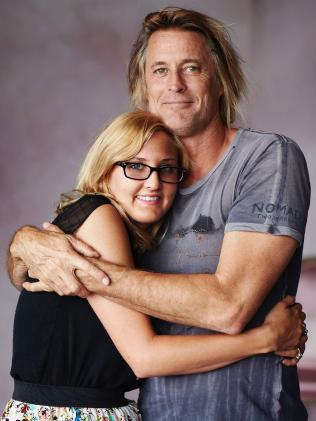

Russell James has never spoken in detail publicly about his daughter Emily’s nine-year battle with mental health issues.

It’s a fact of which the high-profile celebrity snapper, fine arts photographer and human-rights campaigner says he is “quite ashamed”.

But it’s indicative of the stigma still associated with topics such as suicide, self-harm and drug abuse.

This is despite one in five Australians suffering from a mental illness, with the prevalence being greatest among young people aged 18 to 24.

“Mental health is stuck in the dark ages,” James says. “One of the key reasons mental health hasn’t received the same level of attention, funding and research (compared with other medical issues) is that we haven’t listened to the experts calling out for it.

“And, far worse, the stigma associated with mental health issues has prevented us all from putting it front and centre. Shame on me, as I was one of those people.”

James has an international profile for his striking portraits of beauties such as Heidi Klum; his collaborative art project, called Nomad Two Worlds, with indigenous communities; and his books, which have forewords by the likes of Hollywood star Hugh Jackman and Virgin boss Sir Richard Branson.

But behind the glitter and glamour is James’s anguished personal journey with Emily, his first child, who showed signs of mental health problems from a “very young age”.

“She would go from being wildly happy to incredibly morbid,” he says. “She had great struggles keeping relationships and she was fearless to the point of having no apparent regard for her own safety.

“The feedback we always received was that she was just being a kid. Or, if she was unable to adapt at school, then it would be that she was just ‘naughty’.”

James laments that schools simply don’t have the “tools” to identify and properly deal with children suffering from mental health issues.

When Emily was 14, her problems “started to manifest in the most frightening of ways”.

“Her depression and anxiety became so great she would use any drugs put before her,” James says.

“If there was meth available she would use it. If there was heroin she would use it. I was aware she was using drugs, but not the extent until recently — and also how easily they were available.”

James says the situation came to a head when he found her lying on her bed one day with “blood everywhere”.

“I asked her what happened and she said she had taken a stick and hit herself. She did it because it made her feel better,” he says.

“She had tears rolling out of her eyes. I could see she was in agony, but I had no idea what to do.”

Feeling like he was getting nowhere with the medical help his daughter was receiving in WA, James sent Emily to a “wilderness retreat” in the US.

“Wilderness therapy has given my daughter long periods of wellbeing and being at peace with herself,” he says.

“Dedicated professionals take people, ranging from 13 to 35 years of age, into a remote wilderness setting and, working in groups of four, they bring them back to the basics of life.”

James credits the therapy with saving Emily’s life. He says it was the reason she managed to get back into the education system. However, he says his daughter went into a “tailspin” when she came home and “immediately returned to drug and alcohol abuse”. One of those drugs was the extremely addictive stimulant methamphetamine, known on the street as “ice”.

“Meth is a scourge,” James says. “It does irreparable damage, it’s readily available and it’s cheap.”

Prime Minister Tony Abbott this week announced a new federal “ice taskforce” to tackle what he says is a narcotic “far more potent, far more dangerous, far more addictive than any previous illicit drug”.

She had tears rolling out of her eyes. I could see she was in agony, but I had no idea what to do.”

In many ways, James says his struggle with the WA mental health system is best told by comparing the medical journeys of his two daughters.

“In 2008 my youngest daughter (Lola) was taken to a paediatrician with an extended belly and a light fever in New York State,” says James, who splits his time between the US and Australia.

“The doctor immediately ordered her to be taken to a nearby major hospital and within a few hours she received an MRI scan. A specialist oncologist was brought in to review the MRI and informed us that our daughter had extensive tumours and likely a cancer they needed to identify.

“That same night she was taken to a hospital several hundred miles away … within three days we were informed that Lola had a cancer known as neuroblastoma, which is extremely rare and affects about 700 children per year worldwide.

“They literally dissected my daughter over a 12-hour period using human hands, robots, and life-support systems to remove tumours invading from her hips to her upper chest cavity, around her heart and other vital organs.

“During the next couple of years of recovery she was in the care of an oncologist, a gastroenterologist and a tumour review board that consisted of six experts.

“And, by the way, that is the identical care your child would receive in WA if they were diagnosed with neuroblastoma.”

For Emily, with psychological issues, the story could not be more different.

“Emily has been admitted to hospital and mental health facilities more times than I can recall,” he says. “Even after multiple near-death situations and major incidents there was virtually no continuity of care.

“If Emily was admitted to Royal Perth Hospital naked, beaten and in psychosis, the hospital would find no record of a previous admission to Fremantle Hospital for a suicide attempt.

“Then when Emily would be admitted to private care no records would be passed along from the public sector. Emily was assessed again and again from scratch.”

“A horrible, dark ward in the basement of the hospital,” he says. “Just one psychiatrist to visit the ward for one hour  every day … many of the patients drooling in wheelchairs because of the level of medication they were given under a policy of, ‘Let’s keep everybody safe and calm’.”

every day … many of the patients drooling in wheelchairs because of the level of medication they were given under a policy of, ‘Let’s keep everybody safe and calm’.”

James says it broke his heart seeing Emily there and he privately lobbied the Barnett Government to do something about its conditions.

Health Minister Kim Hames tells STM that the ward, which was opened in 1958, is due to be closed in early June. Dr Hames says that patients will be sent to a new $21 million,

30-bed facility at the site.

It’s not just public patients who face challenges. James says the private mental health system in WA is just as under-resourced — and only available to those who can afford it.

And, most frustratingly, he says the medical answer offered for Emily in WA has “almost always” been a “cocktail of pharmaceutical drugs that render her near catatonic”.

“The past nine years have been defined almost exclusively by my daughter’s mental health issues and by the continued misdiagnosis and lack of resources in Australia,” he says.

“My experience with my two daughters has served as a metaphor that has given me shocking perspective.

“For Lola, 190 days and a rare, highly complex disease is identified and a large group of professionals assembled to deal with it.

“She has since gone on to be a national gymnastics competitor and is a straight-A student.

“Meanwhile, Emily has languished for nine years slipping through the cracks of a system, or rather a non-system.”

Australian Medical Association state president Michael Gannon says the lack of continuity of care for mental health patients in WA can be frightening.

“In many ways, it’s a system in crisis,” he says.

“It’s not serving the patients well, it’s not serving the carers well and it’s certainly not serving the doctors who work in it well.”

Dr Gannon says doctors were worried the system was becoming too focused on “low-hanging fruit”, such as patients with low levels of anxiety or depression, rather than the sickest people.

“There needs to be better resourcing for people with severe levels of dysfunction, like schizophrenia or those suffering from ice addiction,” he says.

“We know that even in the private sector the resources available for child and adolescent psychiatry are poor. We also know that there is not enough ‘step down’ capacity for our sickest patients.”

I was willing to steal, borrow, beg — anything to save my daughter’s life. I owed my daughter a chance at living.”

Emily’s bleakest moment came when she suffered a cardiac arrest and contracted a staph infection.

“It is unclear whether she contracted the MRSI during her treatment at the hospital or from drug use,” James says. “I was willing to steal, borrow, beg — anything to save my daughter’s life. I owed my daughter a chance at living.”

James says mental health experts told him Emily would die if she was left in Australia.

After much research, about a year ago he found an “assisted living” program in Sweden for Emily.

“The program she is in is very small and heavily funded,” he says. “It was specifically created in addition to programs that are entirely for either mental health or addiction.

“So often mental health issues lead to addiction and once addiction has taken over it’s impossible to treat the root cause, mental health. So this is an ‘and’ approach.

“What they are doing, though, is really having a go at bringing research and development into this century and out of the dark ages.”

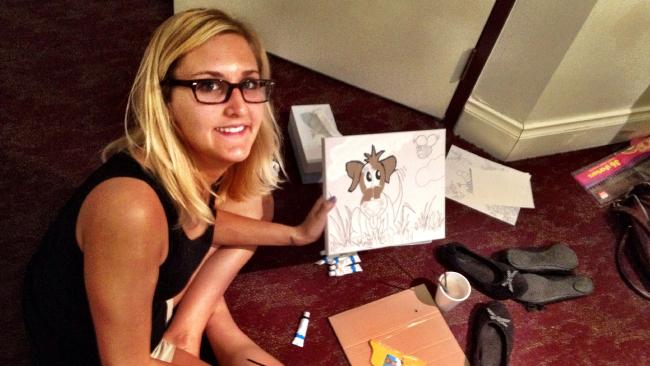

James says his daughter has now reached a point where she is willing to be “very open” about her struggles with depression, eating disorders and drug addiction.

Emily will soon move into her own apartment, where she will still receive about 15 hours of care a week through the Swedish program.

“I can’t tell you the guilt I feel because I was fortunate to find the money to get Emily treatment,” he says.

“We have also had a strong family advocating for her care.

“Most people aren’t so lucky. The end result for them is to likely perish in miserable conditions.”

James says by talking candidly he feels he is finally “taking personal responsibility” for putting mental health on the agenda.

He wants everyone reading his daughter’s story to speak up as well. If enough people share their stories, then maybe the stigma can be broken down.

“WA is a world leader in many health categories,” James says. “However, mental health is stuck in the dark ages.

“The stigma of mental health issues is literally killing millions of people around the world.”

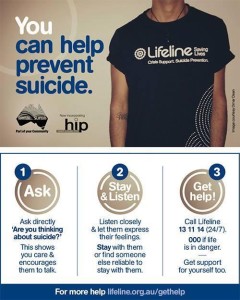

He also wants to raise awareness of how crucial the crisis support service Lifeline WA is. He says its 13 11 14 helpline deserves more government funding and donations from philanthropists.

“My daughter has told me that somebody pushed the Lifeline number into her hand after she was being discharged from a hospital and a couple of months later she found herself homeless, on the streets, in unbearable pain and lost to us and suicide felt like a relief,” James says.

“She called the number and in her own words, ‘It saved my life’.”

James uses another parallel when discussing his motivations for speaking out.

There were about 1150 people killed on our roads last year. This compares with nearly 2500 suicide deaths on average every year.

“Suicide is one of our biggest killers — bigger than the road toll,” James says. “It deserves the level of inquiry, research and understanding we give to road deaths.

“As a community we need to put our heads and hearts together and just get on with it.”

If you need help, contact Lifeline WA on 13 11 14 or at crisischat.lifelinewa.org.au

Reposted with permission from Anthony.

Follow Anthony DeCeglie on Twitter: @AnthDeCeglie

News gleaned from the TV, radio, or Internet can be a positive educational experience for kids. But when the images presented are violent or the stories touch on disturbing topics, problems can arise.

News gleaned from the TV, radio, or Internet can be a positive educational experience for kids. But when the images presented are violent or the stories touch on disturbing topics, problems can arise.

Recent comments